On Line or In Person?

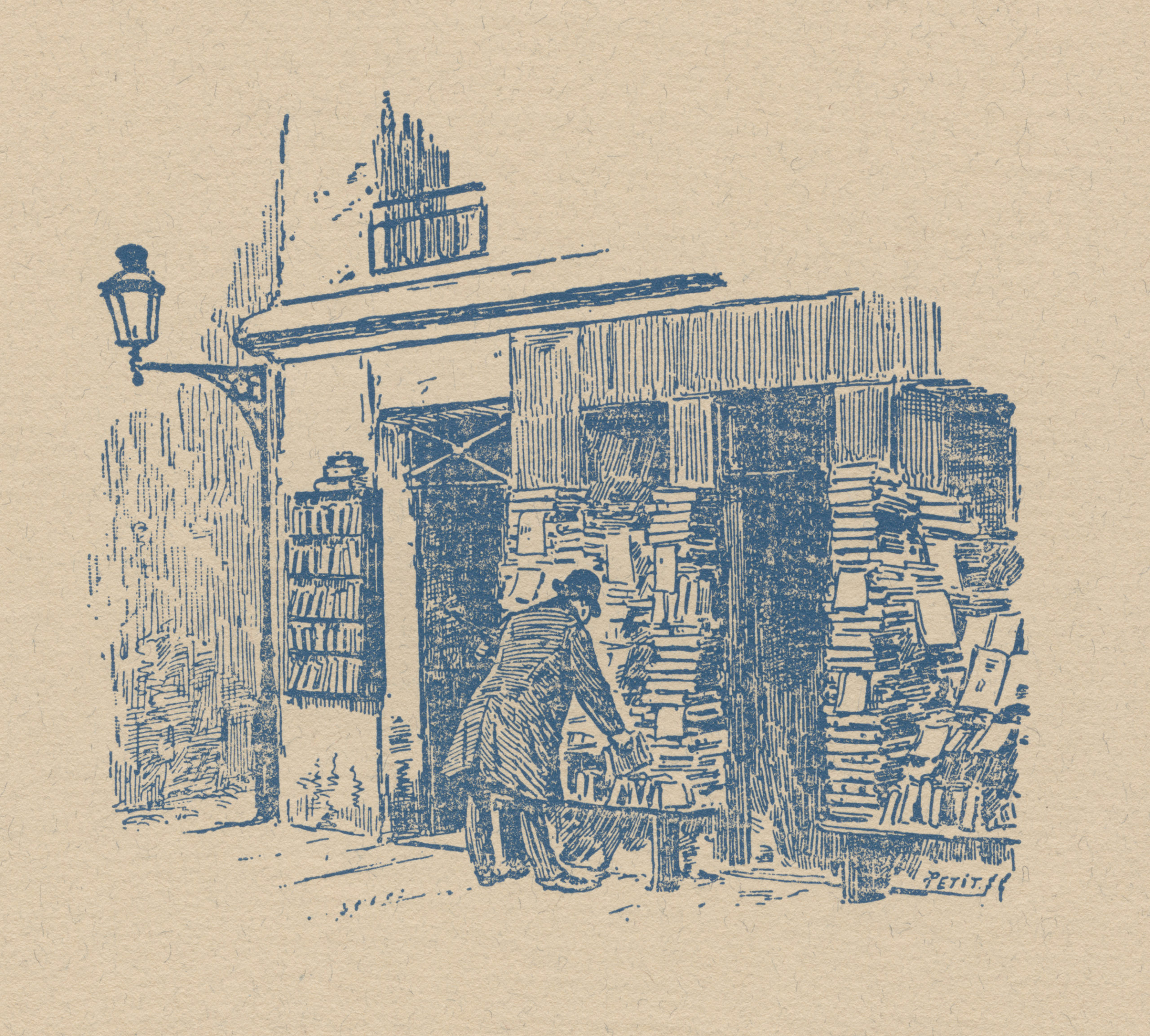

What would bookman William Targ think of digitized rare book collections? A lover of all things physical about books, would he disdain digital collections and exhibits for their two dimensionality and sensory absence? Or, would the profit-driven publisher have understood the potential in new technologies? Probably both.

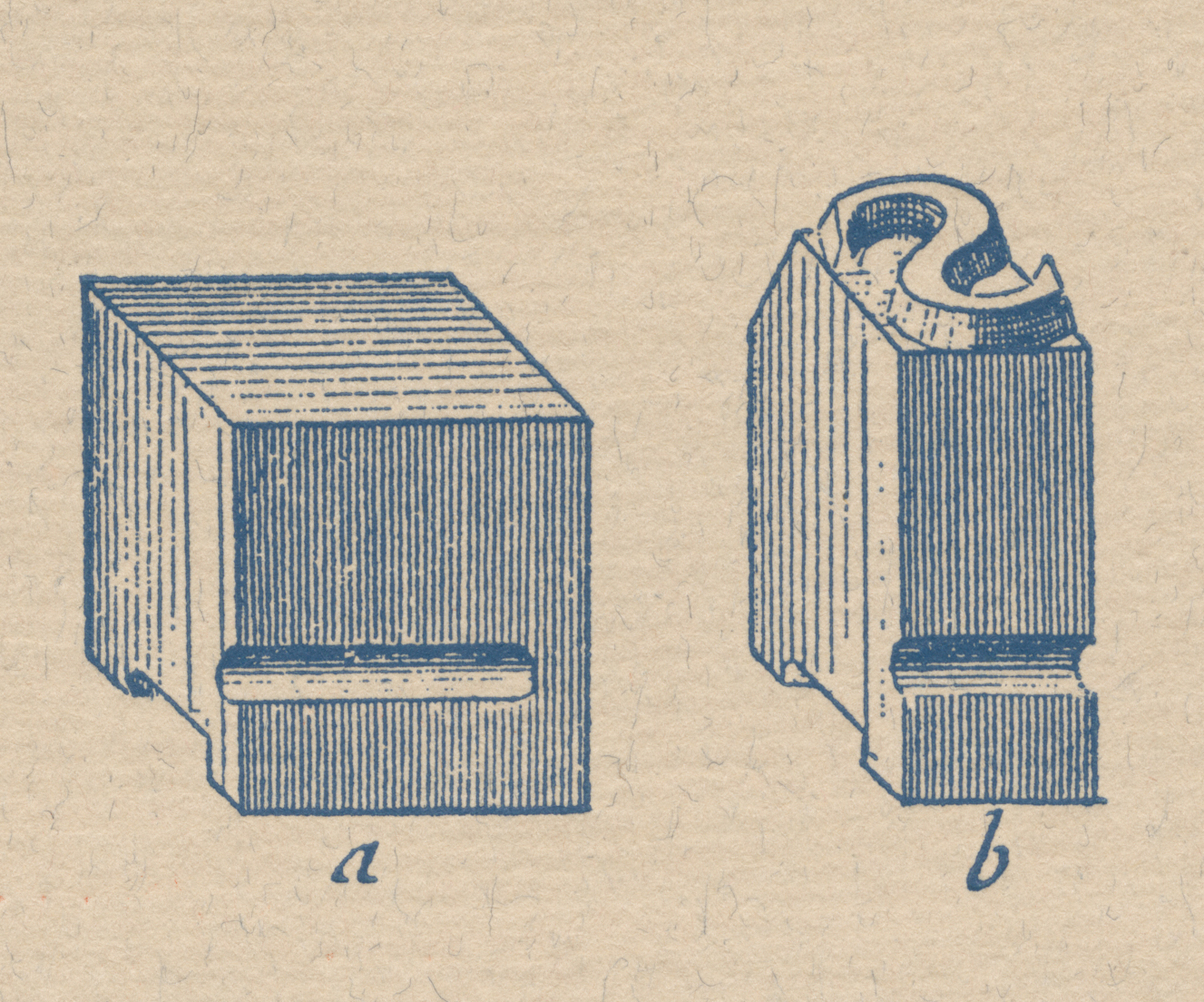

Digitization of rare books and special collections has gone through roughly three stages. In the beginning, granting agencies funded what came to be known as “boutique collections,” selectively digitizing the most visually attractive and valuable gems in a special collection. Targ Editions qualifies as a boutique digitization project in its scope and content.

Digitization then became a preservation tool through which digital copies with detailed descriptions would capture information from fragile originals and reduce the need to physically consult those deteriorating originals.

Soon, however, boutique collections lost favor with researchers who grew frustrated with librarians acting as intermediaries by selecting what would be digitized. Bulk digitization became the norm, expanding from selective displays of visually pleasing gems to a central process in library operations.

But, would researchers glean enough information online to determine what a rare book library holds and how to access it? Special collections users historically have relied on detailed descriptions of individual items, and an opportunity to at least see, if not touch, the physical book.

So, what do users want from virtual rare book libraries, and do digitized collections provide it? Early online users fully exploited zooming, page turning, annotating, and access terms. Users today want a more dynamic, interactive engagement with digitized materials that includes sharing, discussion, tagging, and manipulation. Collaboration through social media and linked data are also important to online users. Additionally, users also expect greater access to “hidden” collections from underrepresented communities or of a more controversial nature, a requisite Targ the risk taker would have understood.

Predictions about the impact of digitization have generally fallen into two camps. Some believe the ease of online access will discourage users from visiting rare book libraries, contenting themselves with a digital representation. Others anticipate and point to increased in-person research queries after digitization projects and online use.

Problems with mass digitization, as some librarians see them, include misinformation and misinterpretation when no librarian is present to assist users. Researchers also miss a sense of community and collegiality once found in a physical research library or reading room.

Perhaps the biggest question is, do the benefits of vastly increased access to many more rare materials online outweigh the loss of intimate tactile engagement with the physical books themselves? Would most booklovers even know Targ Editions exist without online access? Would William Targ care?

Is it coincidental that neighborhoods like Greenwich Village, which have always attracted writers, printers and publishers, now draw digital humanists, e-publishers, and entrepreneurs engaged in massive digitization projects? Targ would have seen the connections, even if he didn’t jump on the computerization bandwagon.